When trying to address a social problem, a frequent response is to simply ask for a new product. When you state it boldly like this, it does sound unconvincing. Social problems are clearly symptoms of interconnected causes and effects that vary in their nature. Some (income inequality, say) are influenced by impersonal macro-trends such as the changing nature of the economy. Others (for example, obesity) reflect forces such as the infrastructure in our cities, habits and consumer marketing.

Despite this, my experience in working in sectors such as humanitarian relief and education is that the allure of shiny new stuff dominates our thinking and actions. Especially amongst those who have the word ‘innovation’ somewhere in their job-title. There is evidence that this bias occurs elsewhere. For example, a recent fascinating study shows the extraordinary weighting of health research towards new drugs. This is at the expense of research into the best ways of influencing the other factors that affect health - for instance, social factors such as having trusted peer support or behavioural factors such as the food you eat and the exercise you take.

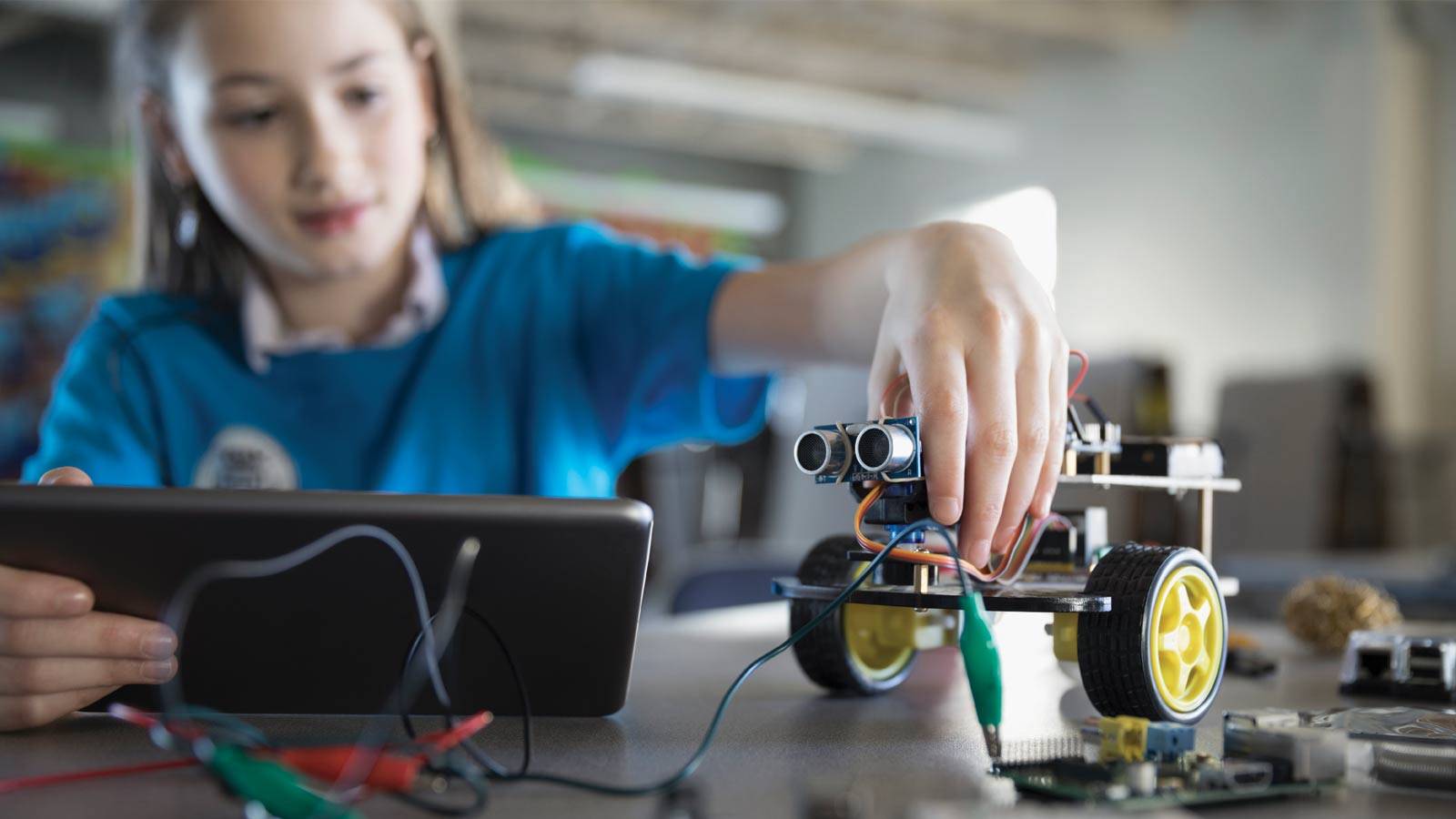

Let me be clear. It is not that there is never a need for new products. We badly need some well-designed adaptive learning tools that handle the particular challenges of learning Arabic (even ones for Arabic maths learners would be a start); we do need better evidence informed interventions for struggling readers and writers; and we definitely need more founders to create outcome focused kindergartens.

My point, though, is that this is rarely enough.

To illustrate this, it’s useful to take three awesome product inventions -- the iPhone, electricity and shipping containers -- and to track the impact that they have made. Attention to their history shows that it is the bundling of innovations, often very different in their nature, that delivers change.

Apple’s success in changing how we consume music was a combination of product (the iPhone) and service (iTunes) innovation. There was also a change in purchasing habits that Napster had already begun and new pricing deals with the music industry.

The big surge in global trade came about when containerisation was coupled with the ICT revolution of the 1990s and a series of trade liberalisation rounds (something beautifully examined in this book).

Similarly, the electrification of US households allowed the widespread use of labour saving devices such as washing machines. However the effect on female participation in the workforce was not visible until equal pay legislation, female role models, and the simple need to increase household income, spurred female work outside of the home.

One of my intellectual heroes, Geoff Mulgan, once proposed a simple 2x2 framework that maps transformative changes such as those described above onto four categories:

- New Products or Services (e.g., a drug, a new student text-book, or an assessment service)

- New Behaviours and Habits (e.g. surgeons wash their hands or we get into the habit of cycling to work)

- New Policies and Regulations (e.g., a regulation around staffing ratios in kindergartens)

- Recalibrated Markets (e.g., taxes, subsidies, and market guarantees that change existing financial incentives)

Change, he argues, arises from attending to two or more of these elements. For example, a new set of literacy resources that privileges the systematic teaching of phonics (a product) is accompanied by high-quality teacher professional development (a service). Alongside this, a new school accountability measure (a change in regulation) holds schools to account for acting on what works. All this is should be aligned with a reformulated curriculum, so that all elements of the system are signalling what is important, and providing the right mix of pressure and support to make change happen.

Sometimes there is nothing as practical as a little bit of theory!

At the Queen Rania Foundation our goal is to craft responses that reflect the complex nature of the challenges we’re addressing. We’ve always carried out research, policy work and programmatic activity, but we’re now consciously bringing them together. This now starts from the get go when we begin to analyse a problem we want to address.

It also extends to designing responses that recognise that inventing a product is frequently not enough. For example, you may need to add in a service to make sure it is used effectively - which gives you a programme.

Sometimes, a programme will not be enough if the existing policies, habits, and financial incentives mitigate against its effectiveness. For example, a programme that encourages more group work in school is going to have a tough time being effective if the curriculum discourages it, or if it does not address the fact that teacher habits privilege quiet work at your desk.

This type of thinking isn’t new (it’s common in areas such as military planning or the tracking of health epidemics.) It’s also not that hard to do. However, it is infrequently applied in education policy making and implementation. Our belief is that learners deserve that we do better at this.